Dot Gain and Its Impact on Print Quality

Dots per inch (DPI) is a measure used to describe the resolution of a digital print and the printing resolution of a hard copy. It relates to dot gain, the increase in the size of halftone dots during printing, caused by ink spreading on the media surface. Printers with higher DPI generally produce clearer and more detailed output, although the actual DPI measurement can vary depending on print mode and driver settings. The range of DPI a printer supports is largely influenced by its print head technology.

DPI vs. PPI: Achieving Quality Output

To achieve similar quality output to a video display, a printer often needs a significantly higher DPI than the pixels per inch (PPI) measurement of the display. This is due to the limited range of colors each dot can produce on a printer. At each dot position, basic color printers can print no dot or a dot of a fixed ink volume in four color channels (typically CMYK: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black), resulting in up to 16 colors. However, the actual number of discernible colors can be lower, depending on various factors like the strength of the black component and the overlay strategy used.

Advanced Color Printing Techniques

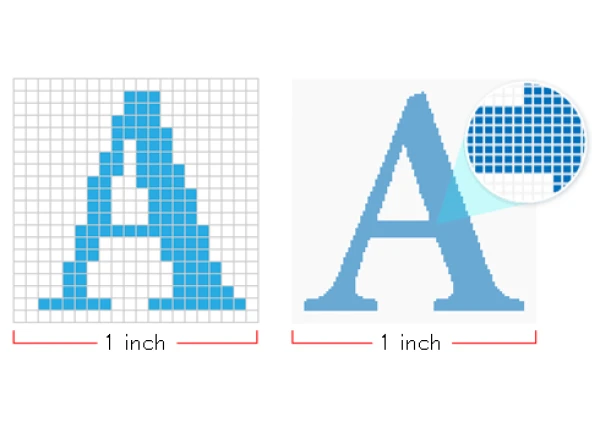

While some color printers can produce variable drop volumes and use additional ink-color channels, the number of colors remains less than on a monitor. Therefore, printers often rely on halftone or dithering processes to create additional colors, using a high base resolution to "fool" the human eye into perceiving a smooth color patch. This process may require a region of four to six dots to reproduce the color of a single pixel accurately.

Modern Printer Resolutions and Historical Context

For example, a 100-pixel-wide image might need 400 to 600 dots in the printed output. If this image is to be printed in a one-inch square, the printer must be capable of 400 to 600 DPI. Modern entry-level laser printers and utility inkjet printers typically have output resolutions of 600 DPI (sometimes 720), with high resolutions of 1200–1440 and 2400–2880 DPI being common. This is a significant improvement from the 300–360 (or 240) DPI of early models and the approximately 200 DPI of dot-matrix printers and fax machines. Early printers produced documents with a characteristic "digitized" appearance due to coarse dither patterns, inaccurate colors, loss of photograph clarity, and jagged edges on text and line art.